Have you ever sat in a data structures or algorithms class wondering why the teacher spend so much time on graph theory? Isn’t graph theory only useful for cracking the code interview? (I still can’t believe a course like this exists) There’s nobody in their right mind that would use graph to solve real-world problems? My time should be spent learning something useful like how to build a Javascript framework.

Wrong! Wrong! (And most definitely) WRONG!!

Graph are ubiquitous in computer science: databases, compilers, and, as my last article established, build systems. Hell, if I was a betting man, I’d say that Skynet will probably be born out of an out-of-control TensorFlow (or whatever en vogue machine learning framework at the time) graph that will start to want to link up with EVERYTHING.

My point is: learning about graphs and how to manipulate them is a critical skill to ensure our children lives in a world free of despotic AI overlords. If you want an example of how to do so, read on.

Compiling a C++ application (the right way)

Going back to our problem of compiling C++ files. We just built a dependency graph indicating what we should be compiling. Now, we have to walk through it.

Normally at this point, I should be talking about how recursion is the way to go since our dependency graph is essentially a tree. However, with all the constraints we put on our build system, we can go for a far more straightforward solution. This will save us a lot of trouble since recursion can be tricky and result in awakening nameless fear like the dwarves did in the mines of Moria if we’re not careful enough.

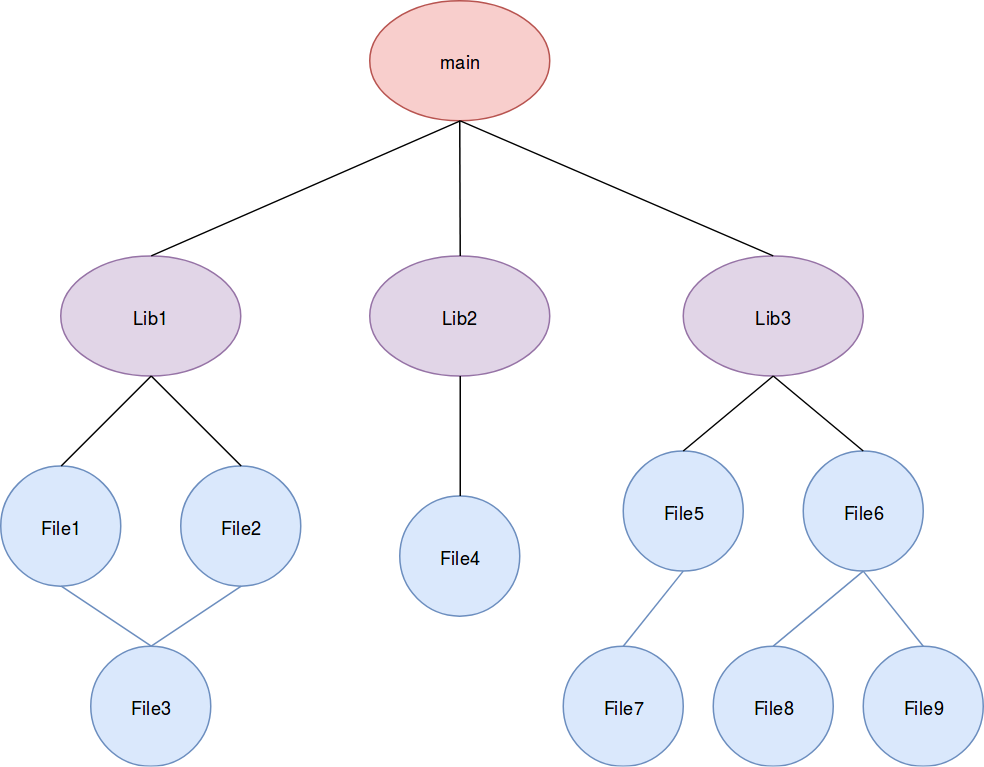

However, remember the shape of our dependency graph. At the top, we have the main node to which we’ll link every library file produced. Then, at the level just below, we have subgraphs that will be used to create the library files.

With such a flat interpretation, a breadth-first traversal is more than adequate to accomplish our task.

Here’s how we’ll attack it. First, some definitions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

using DGN = DependencyGraphNode;

using NodePtrQueue = std::queue<const DGN*>;

using NodePtrSet = std::set<const DGN*>;

using NodePtrVector = std::vector<const DGN*>;

bool Compile(const DependencyGraph& graph, const std::string& appName)

{

Then, a simple sanity check to make sure we don’t perform more work than necessary.

1

2

3

4

5

// Is there anything to do?

if (graph.IsEmpty())

{

return false;

}

As I said earlier, every subgraph below the root node will be used to generate a library file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

const DGN& root = graph.GetRoot();

std::vector<std::string> libFiles;

// Generating a lib file per subgraph linked to the root node

for(const auto& child : root.GetChildren())

{

Here’s the fun part. Since we have settled on no further partitionning of these subgraphs, we only need to walk through them to collect their constituant nodes. An effortless way to accomplish that is to ask a node about its children when we visit it and note down these children in a work queue to also visit them later on. For the more visually inclined, this website offers great visualizations of many algorithms including breadth-first graph traversal.

Translating the above description into code might yield something like this for our use case:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

// Collecting all nodes in subgraph

const NodeVector& childNodes = child.GetChildren();

NodeSet nodeSet{childNodes.cbegin(), childNodes.cend()};

NodeQueue workQueue{nodeSet.cbegin(), nodeSet.cend()}

// Using an indice to avoid bad surprises that could be caused

// by iterator invalidation

size_t nodeIdx = 0;

while(nodeIdx < workQueue.size())

{

const NodeVector& children = nodes[nodeIdx].GetChildren();

for(const auto& cNode : children)

{

// Reject all duplicates

if(nodeSet.insert(cNode))

{

workQueue.push(cNode);

}

}

++nodeIdx;

}

Notice two little optimizations that I’ve used in the code above. First, I made sure that we won’t process a node multiple times by using std::set to reject duplicates insertion in our work queue. Second, I made it so no node would be copied by working on pointers to the actual nodes. I put them here if only to make you think about issues that may plague you when you try to scale a build system.

Now, at a high level, creating the actual library file is actually quite easy. Just use some magical function (read: no way this can be done in a portable fashion, so I’ll refrain from presenting an actual implementation for fear of offending anyone) to produce object files. Afterwards, aggregate those object files into a library file with some more magic.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// Producing object files

std::vector<std::string> objFiles;

std::transform(nodes.begin(), nodes.end(),

std::back_inserter(objFiles),

[](const DGN& node)

{

return CompileFile(node.GetFile());

});

libFiles.emplace_back(LinkToLibrary(objFiles));

}

When you finally go out of that loop, a final magic trick will deliver us the promised executable.

1

2

return LinkToExecutable(libFiles, root.GetFile(), appName);

}

Handling Dependencies

I hear you say: “But what if my subgraphs aren’t flat? How do I handle dependencies in that case?”. I’ll be honest, I’m tempted to leave that as an exercise to the reader. But I’m here to teach and I won’t be caught doing an half-assed job. I’ll fully ass my job.

The trick here is that the dependency graph of a source code repository a directed acyclic graph. Consequently, an ordering of its vertices can be obtained via topological sorting.

Now, it’s up to you to choose where you’ll fit this sorting in the build algorithm. You could either use it on the nodes collected by the breadth-first traversal or, if you happen to have a subgraph abstraction, you could directly pass it to a topological sorting function that would give you back an ordered sequence of nodes. In any case, the result would be a sequence of nodes that could then be fed to the CompileFile function as shown above

Coming up next: More threads, more fun!