All the code for this article can be found here.

Have you ever asked yourself: how do regexes works? Or, even better, have you ever thought that you could totally implement a regex engine that would be faster than what powers std::regex? If not, than you’re probably took a wrong turn somewhere on the interwebs and you should probably move along.

For those of you performance freaks that kept on reading, let me share some experiments I did with bringing a regex engine on the GPU using C++AMP.

The Aho-Corasick string matching algorithm

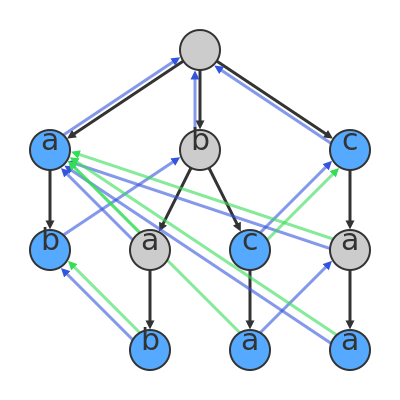

At the heart of our regex engine will be the Aho-Corasick (AC) string matching algorithm. Briefly, this algorithm builds a state machine resembling a trie which is then used to match patterns on a given string. In other words, each state in the AC state machine corresponds to a character that can be matched given the pattern(s) fed to the algorithm. Between each pair of these states there can be an edge that either signifies that:

- The two states linked together represents a valid sequence of characters in a matched string.

- There was a problem fully matching a sequence so we’re backing up to the state which is the biggest prefix of what we succeeded to match.

As an example (shamelessly taken from Wikipedia), say we have the following pattern : “a|ab|bab|bc|bca|c|caa”. This will be used to construct this state machine:

If you prefer code to pictures, here’s how an AC-using regex would be set up:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class StringSearcher

{

private:

static const unsigned NB_ASCII_VALUES = 128;

std::vector<std::array<int, NB_ASCII_VALUES>> mTransitionMatrix;

std::vector<int> mOutputTable;

std::vector<std::string> mDictionary;

In order, we have:

mTransitionMatrix: The state machine represented as an adjacency matrix where rows correspond to states an columns correspond to possible state transition given an ASCII character.mOutputTable: A simple table to identify if a state is a complete match.mDictionary: A list of all possible patterns that we’re currently trying to match.

Once we have the representation down, we need some helper functions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

private:

void AddState()

{

// Creating a new state filled with null transitions

mTransitionMatrix.emplace_back();

mTransitionMatrix.back().fill(-1);

// Also, this state does not represent a complete match

mOutputTable.emplace_back(0);

}

The first one will be there to help us add a blank state to our state machine.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

void AddSearchPattern(const std::string& pattern)

{

// Nothing to do here

if (pattern.empty())

{

return;

}

// Enhancing our state machine with the input pattern

int currentState = 0;

for (const auto& chr : pattern)

{

if (mTransitionMatrix[currentState][chr] == -1)

{

mTransitionMatrix[currentState][chr] = mTransitionMatrix.size();

AddState();

}

currentState = mTransitionMatrix[currentState][chr];

}

// At the end of the pattern we have a match

mOutputTable[currentState] |= (1 << mDictionary.size());

// Don't forget the pattern we can match

mDictionary.push_back(pattern);

}

The second helper function will be responsible of adding new patterns to search for in our regex engine. This will be done by adding states when necessary and adding transitions between states based on input characters.

With these helper functions, we can now define our regex’s constructor.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

public:

explicit StringSearcher(const std::string& patternStr)

{

// Adding the root state

AddState();

// Since we implement alternative ("|"), we split the

// pattern using "|" as a delimiter

std::stringstream stream{ patternStr };

std::string temp;

std::vector<std::string> patternVec;

while (getline(stream, temp, '|'))

{

patternVec.push_back(temp);

}

// Each alternative pattern is then added to the regex engine

for (const auto& pattern : patternVec)

{

AddSearchPattern(pattern);

}

}

One thing you may notice is that I didn’t introduce back edges in the AC state machine like I’m supposed to. This was intentional since we won’t be needing it for what we’re about to do.

Optionally, readers are encouraged to implement the AC failure function as an exercise. Another cool thing to do is to implement other special character like “+” that I left out of the present implementation.

(I won’t lie, this is quite fun to finally be the one leaving holes in his article for “educational” purpose and definitely not because I’m lazy).

Adding a match

Before continuing any further, I want to introduce the data type which will contain the result of a successful pattern match. There’s not really much to mention about it but it’s important to introduce it for the coming string matching algorithms.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

struct Match

{

Match() = delete;

Match(unsigned start, unsigned length, const std::string& pattern)

: Start{ start }, Length{ length }, Pattern{ pattern } { }

unsigned Start;

unsigned Length;

std::string Pattern;

};

Now back to the main event!

Celebrating failure

Right about now, you should be wondering: “How can we parallelize the computations done by the AC state machine?”. The answer is: let’s give up and fail!

In all seriousness tough, failing, not giving a damn about it and moving on is actually the very premise behind the Parallel Failureless Aho-Corasick (PFAC) algorihtm (I encourage you to check out [1] and [2] where I first learned about this algorithm).

The way it works is as follows:

- Have each thread start at a given index in the string to match.

- If there’s a match, record it.

- Whether there’s a match or not, move on to the next index for the thread

See, failure is not really failure when we can keep going forward (there seems to be a life lesson here but it’s totally lost on me).

An implementation of this idea would look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

std::vector<Match> SearchMultithreadCPU(const std::string& str)

{

// Some structures we'll need

std::vector<std::thread> searchThreads;

const auto nbThreads = std::thread::hardware_concurrency();

const auto strSize = str.size();

std::vector<Match> matches;

std::mutex matchMtx;

// We'll start as many threads as there are hardware threads

for (size_t iThread = 0; iThread < nbThreads; ++iThread)

{

searchThreads.emplace_back(

[this, iThread, &nbThreads,

&strSize, &str, &matches, &matchMtx]()

{

// Initially start at the thread index

size_t currentStrIdx = iThread;

while (currentStrIdx < strSize)

{

int currentState = 0;

for (size_t iStr = currentStrIdx; iStr < strSize; ++iStr)

{

currentState = mTransitionMatrix[currentState][str[iStr]];

// Nothing matched, shamefur dispray, commit sudoku

if (currentState == -1)

{

break;

}

// Matched a character but not in a matching state,

// let's continue

if (mOutputTable[currentState] == 0)

{

continue;

}

// If we reach this point, it means we have a complete match

for (auto iDict = 0; iDict < mDictionary.size(); ++iDict)

{

if (mOutputTable[currentState] & (1 << iDict))

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(matchMtx);

const std::string& matchedPattern = mDictionary[iDict];

const size_t matchedLength = iStr - currentStrIdx + 1;

matches.emplace_back(currentStrIdx,

matchedLength,

matchedPattern);

}

}

}

// Let's keep going

currentStrIdx += nbThreads;

}

});

}

// Cleanup

for (auto& th : searchThreads)

{

th.join();

}

return matches;

}

C++AMP

Alright, last stop before we implement our regex engine on the GPU.

C++ Accelerated Massive Parallelism (C++AMP) is an open standard, meaning anybody can access it and implement it, (and some aready did) by Microsoft that specifies language extensions and a small library to enable (mostly) painless computations on the GPU. To give you an overview of this technology, here’s an annotated version (by yours truly) of the “Hello world” example on the C++AMP team’s blog.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

#include <iostream>

// The C++AMP library is contained in amp.h

#include <amp.h>

// Everything is contained in the concurrency namespace

// (like other Microsoft parallel technologies such as PPL)

using namespace concurrency;

int main()

{

int v[11] = {'G', 'd', 'k', 'k', 'n', 31, 'v', 'n', 'q', 'k', 'c'};

// This is our view of (or reference to if you prefer)

// the data on the GPU. It has a type, a dimension (1 by default)

// and is initialized with a data structure on the CPU

array_view<int> av(11, v);

// Basic parallel_for_each with a few twists:

// - restrict(amp) tells it to execute its body on the GPU. This will

// implicitly transfer av's content to the GPU.

// - its number of iteration is the length of av (av.extent)

// - each iteration will receive an index (idx)

// going from 0 to av.extent-1

parallel_for_each(av.extent, [=](index<1> idx) restrict(amp)

{

av[idx] += 1;

});

// Right here, after the execution of parallel_for_each, av will

// be synchronized on the CPU i.e. the modifications done on the

// GPU will be visible to CPU code allowing us to print "Hello world"

// down below.

for(unsigned int i = 0; i < 11; i++)

{

std::cout << static_cast<char>(av[i]);

}

}

There’s of course more to it that what I just showed but for our current needs it will be plenty enough.

Also, this technology seems to have been abandoned since 2014 (last time the C++AMP team’s blog has been updated), which is a damn shame if you ask me. Still, I had wanted to have a go at it for a long time and this project was the perfect excuse.

How to fail faster

Now that we finally have everything we need to implement PFAC on the GPU, let’s get to work!

First, we’ll create array_views of the structures (state machine and all) need for the regex search. Most of the time, this will be straightforward.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

std::vector<Match> SearchAMP(const std::string& str) const

{

using namespace concurrency;

const unsigned strSize = str.size();

const unsigned dictSize = mDictionary.size();

array_view<const int, 1> outputTableView(mOutputTable.size(),

mOutputTable.data());

array_view<const int, 1> strView(strIntVec.size(), strIntVec.data());

But we’ll need to give our transition matrix a special treatment. The fact is that C++AMP only deals with contiguous data structures. That means that a std::vector of std::array, basically a pointer to an array of pointers, can’t be used as is to initialize an array_view. However, fixing this problem is quite easy as we only need to flatten our transition matrix before constructing our view.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// C++AMP needs dense data. Since the transition table isn't dense,

// we have to flatten it before moving it to the GPU

std::vector<int> flatTransitionTable;

flatTransitionTable.reserve(

mTransitionMatrix.size() * NB_ASCII_VALUES);

for (const auto& row : mTransitionMatrix)

{

flatTransitionTable.insert(flatTransitionTable.end(),

row.begin(),

row.end());

}

array_view<const int, 2> transitionTableView(

mTransitionMatrix.size(),

NB_ASCII_VALUES,

flatTransitionTable);

Then there’s the problem of transferring the string on which will perform the search to the GPU. You see, C++AMP data structures can only be typed with something whose size is a multiple of the size of an int. And clearly, char doesn’t fit that requirement. So we have two options here: wasting space by using ints to hold our chars or packing our chars into ints. It goes without saying to we’ll go for the second option.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

// To not waste any space, we'll pack the characters of the

// string argument into integers

std::vector<int> strIntVec;

strIntVec.reserve((strSize + 3) / 4);

for (size_t iStr = 0; iStr < strSize; iStr += 4)

{

int packedChars = 0;

packedChars = str[iStr];

packedChars <<= 8;

packedChars |= str[iStr+1];

packedChars <<= 8;

packedChars |= str[iStr+2];

packedChars <<= 8;

packedChars |= str[iStr+3];

strIntVec.push_back(packedChars);

}

Last but not least, we’ll define a structure to contain our pattern matches. This will be a matrix where the rows will represent a pattern to match and the column will represent a character in the input string. When a match will be made, we’ll write the length of the match in the cell corresponding to the pattern’s row and the beginning character’s column.

1

2

std::vector<int> results(strSize * dictSize, -1);

array_view<int, 2> resultsView(strSize, dictSize, results);

This may look like we’re doing do much redundant work here. Why not just build most of these views when constructing our regex engine? Well, the thing is that a lambda marked with restrict(amp) can’t capture this so member variables are a no go. This means that there’s pretty much no way that we could pre-initialize our structures on the GPU with C++AMP.

With that being said, let’s finally move on to the implementation of PFAC on the GPU.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

parallel_for_each(

extent<1>(strSize), // Iterating over the size of the input string

[transitionTableView, outputTableView, resultsView, strView, strSize]

(index<1> idx) restrict(amp)

{

// Each parallel invocation of this lambda will start its

// pattern matching at a different character

const int strStartIdx = idx[0];

int currentState = 0;

int index = 0;

int currentChar = 0;

for (unsigned iStr = strStartIdx; iStr < strSize; ++iStr)

{

// Accessing a character

index = iStr / 4;

currentChar = strView[index] >> (8 * (3-(iStr % 4))) & 0xFF;

currentState = transitionTableView[currentState][currentChar];

// Nothing matched, shamefur dispray, commit sudoku

if (currentState == -1)

{

break;

}

// Matched a character but not in a matching state, let's continue

if (outputTableView[currentState] == 0)

{

continue;

}

// If we reach this point, that means we have a complete match

for (int iDict = 0; iDict < resultsView.extent[1]; ++iDict)

{

if (outputTableView[currentState] & (1 << iDict))

{

resultsView[strStartIdx][iDict] = iStr - strStartIdx + 1;

}

}

}

});

// Magic synchronization of the results here!

// Creating the matches

std::vector<Match> matches;

for (size_t iStr = 0; iStr < strSize; ++iStr)

{

for (size_t iDict = 0; iDict < dictSize; ++iDict)

{

const int matchLength = results[(iStr * dictSize) + iDict];

if (matchLength > 0)

{

const std::string& matchedPattern = mDictionary[iDict];

matches.emplace_back(iStr, matchLength, matchedPattern);

}

}

}

return matches;

Results

For the experimental setup, I’ve decided to take a somewhat long text and create a pattern out of some of its characters. Can you guess which book I’ve used?

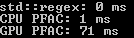

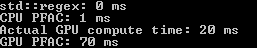

As our baseline, we’ll use std::regex_search. This will then be compared to both the multithreaded PFAC on the CPU and the C++AMP implementation of PFAC.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

int main()

{

const std::string pattern = "Helen|Achilles|Ulysses|Hector

|Andromache|Patroclus|Ajax

|Priam|Agamemnon|Cassandra";

StringSearcher searcher{ pattern };

// Reading Homer

std::string textStr;

std::ifstream stream("text.txt");

if (stream)

{

textStr = static_cast<std::ostringstream&>(

std::ostringstream{} << stream.rdbuf()).str();

}

else

{

return 1;

}

{

std::smatch match;

std::regex re{ pattern };

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::regex_search(textStr, match, re);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::cout << "std::regex: "

<< std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(

end - start).count()

<< " ms\n";

}

{

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

searcher.SearchMultithreadCPU(textStr);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::cout << "CPU PFAC: "

<< std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(

end - start).count()

<< " ms\n";

}

{

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

searcher.SearchAMP(textStr);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::cout << "GPU PFAC: "

<< std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(

end - start).count()

<< " ms\n";

}

return 0;

}

Now how well did we do against std::regex?

*drumrolls*

Unfortunately, not so great. Even when I add a timer to get the actual computation performed on the GPU (see below) what I record still doesn’t match std::regex’s performance.

What else could have I done?

Even tough the end result is a bit disappointing it is not entirely unexpected and there are two big reasons for that.

First, and I knew this when I started this little project, the algorithm that I’m using, the AC algorithm, is not the most efficient for implementing a regex engine. So the fact that I’m not starting from the most effective regex engine might’ve played against me.

On a side note, for those interested in regex implementation, here are good starting points.

The second explanation for the results we’ve seen that I can think of is that C++AMP wasn’t as easy to use as I thought and for all the syntatic sugar it offers, it doesn’t offer much when it comes to irregular computations on the GPU. It did make me think that eschewing syntactic sugar in favor of using lower level tools allowing us to have finer-grained control would be the way to go.

In the end, I still believe that the idea to parallelize regex matching based on the input string is a great idea and it kinda made me want to try to test it in a standard std::regex implementation.