All the code for this article can be found here.

Here’s an idea for you: wouldn’t it be nice if a mutex could warn us that we’re going to deadlock the very moment we’re trying to acquire it? It may sounds far-fetched but it is very doable but it is probably quite simpler than you imagine.

A bit of background

Traditionally, we define a deadlock as the situation in which each member of a group of threads is waiting on a resource held by another member of said group. For those more visually-inclined, here’s what it looks like through the lens of a resource allocation graph.

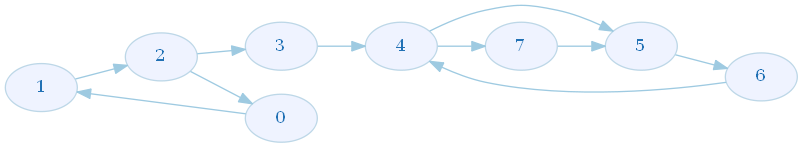

While explicit, this graph is a bit too much for what we’re going for in this article. Instead, we’ll use a version of this graph where the resource ownership is implicit. We thus end up with what is commonly referred to as a wait-for graph.

Once we have this graph, it naturally follows that we only have to find out if it contains at least a cycle to say if we’re going to deadlock or not.

The wait-for graph

To quickly prototype our idea, we’ll use the Boost Graph Library (BGL). Our chosen graph representation will be a labeled graph where each vertex is labeled by a thread ID.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

using ThreadID = std::thread::id;

class WaitForGraph

{

private:

using GraphT = boost::labeled_graph<

boost::adjacency_list< // Graph representation

boost::vecS, // Edge storage

boost::vecS, // Vertex storage

boost::directedS>, // Directed graph

ThreadID>; // Vertex label

In addition of an internal graph, the WaitForGraph will also contain a mutex to moderate all the concurrent accesses it’ll be subjected to.

1

2

3

private:

std::mutex mMutex;

GraphT mGraph;

For the purpose of our demonstration, the WaitForGraph instance we’ll use will be at the global scope. Such being the case, I went ahead and made it a singleton. This comes with the added bonus that it will be inherently thread-safe since the initialization of local static variables is thread-safe as per the C++ standard since C++11.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

public:

static WaitForGraph& get()

{

static WaitForGraph graph;

return graph;

}

public:

WaitForGraph() = default;

WaitForGraph(const WaitForGraph&) = delete;

WaitForGraph& operator=(const WaitForGraph&) = delete;

WaitForGraph(WaitForGraph&&) = delete;

WaitForGraph& operator=(WaitForGraph&&) = delete;

We’ll defer the insertion and deletion of a vertex to BGL.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public:

void AddNode(const ThreadID& tid)

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lg{mMutex};

boost::add_vertex(tid, mGraph);

}

void RemoveNode(const ThreadID& tid)

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lg{mMutex};

boost::clear_vertex_by_label(tid, mGraph);

}

Now for the fun part. When adding and edge between to vertices, we’ll want to make sure that doing so won’t introduce a cycle in the graph (i.e. we’re not creating a deadlock). Luckily for us, BGL offers a function that can detect the strongly connected components (SCCs) in a graph. For those lacking in graph theory, a SCC is a subgraph in which every vertex is reachable from every other vertex.

In the example above, we have two SCC. One is composed of the vertices 0,1 and 2 and the other one is made up of the vertices 4,5,6 and 7.

It’s quite plain to see that a SCC in a directed graph like ours means that there is a cycle in the graph.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public:

void AddEdge(const ThreadID& fromTID, const ThreadID& toTID)

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex>{mMutex};

boost::add_edge_by_label(fromTID, toTID, mGraph);

std::vector<int> sccs(boost::num_vertices(mGraph));

if (boost::connected_components(mGraph, sccs.data()) != 0)

{

std::cerr << "DEADLOCK DETECTED:\n"

<< "Thread 1 ID: " << fromTID << "\n"

<< "Thread 2 ID: " << toTID << "\n";

}

}

While we could certainly be more clever in our management of deadlocks, our goal here is simply to warn the user that a deadlock is occuring in the application. Consequently, the message proposed here will do the job.

The DDMutex

To build a deadlock-detecting mutex we’ll need three things. First, a real mutex to make it work (duh!). Second, we need a way to identify the current owner of the mutex such as an ID. And, finally, third, we need a structure that will tell us if the mutex is presently owned.

1

2

3

4

5

6

class DDMutex

{

private:

std::mutex mMutex;

ThreadID mOwnerID;

bool mIsOwned = false;

Going into the Lock method, we’ll want to make sure that there is a vertex for the current thread in the WaitForGraph. This will be done by unconditionally adding a vertex to the WaitForGraph. Worry not, this won’t create duplicate vertices since a boost::labeled_graph guarantees that no two vertices shall have the same label.

After this is done, if the mutex is currently owned by some other thread, we’ll add an edge between the vertices representing the owner thread and the current thread. This will fire the deadlock detection algorithm of the WaitForGraph. If worst comes to worst, then we’ll be shout at that we’re creating a deadlock.

Afterwards, we can lock the DDMutex and update its internal state to make it clear it’s owned by the current thread.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public:

void Lock()

{

ThreadID currTID = std::this_thread::get_id();

WaitForGraph::get().AddNode(currTID);

if (mIsOwned)

{

WaitForGraph::get().AddEdge(mOwnerID, currTID);

}

mMutex.lock();

mOwnerID = currTID;

mIsOwned = true;

}

Finally, the Unlock method will undo what the Lock has done.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public:

void Unlock()

{

WaitForGraph::get().RemoveNode(mOwnerID);

mIsOwned = false;

mMutex.unlock();

}

One thing to note is that I’ve chosen to bluntly remove the vertex representing the owner from the WaitForGraph. I know could’ve been way smarter about my management of the WaitForGraph but let’s say I decided to left it as an exercise to the reader.

Putting it to the test

if we run the following program:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

using namespace std::chrono_literals;

int main()

{

DDMutex m1, m2;

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

threads.emplace_back([&m1, &m2]()

{

m1.Lock();

m2.Lock();

std::this_thread::sleep_for(1s);

m1.Unlock();

m2.Unlock();

});

threads.emplace_back([&m1, &m2]()

{

m2.Lock();

m1.Lock();

std::this_thread::sleep_for(1s);

m2.Unlock();

m1.Unlock();

});

for (auto& th : threads)

{

if (th.joinable())

{

th.join();

}

}

return 0;

}

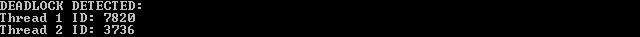

This is what we can end up with: