One of the less talked about features of C++11 are unrestricted unions. In this post, I’ll explain what they are, how they’ve been useful to me and why we’ll quickly forget about them in the future.

Story time

Once upon a time, back when I was working on TosLang, I set out to write an interpreter for the language. Not to go into the fine details of the interpreter implementation, which would fill a blog post by itself, I’ll just say that it was designed as a simple AST-walking interpreter. To give a visual example of what I mean, let’s take the following program:

1

MyInt = MyOtherInt + 2;

and turn it into an AST:

Then, to interpretet the program, I just needed to use a simple visiting scheme to associate a value to each node and perform some actions if needed (like anything to do with I/O for example).

As you can see, I needed an abstraction over a value that could be produced by an AST. A value that, following TosLang’s grammar, could be either a integer, a boolean or a string. In other words, I needed what we call in type theory a sum type i.e. a data structure that can hold a value that can be of a fixed number of different types.

Enter the unrestricted union

Fortunately, C++ (in fact, I shoud say C) already offers us a mean by which to express a sum type: the tagged union. To do so, one only has to encapsulate in a class/struct a value (held in a union) and a tag (usually an enum value) indicating what the type of the value is. Below is an concrete (academic) example of a tagged union.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

struct TaggedUnion

{

enum Type { BOOL, INT };

Type mType;

union

{

bool bVal;

int iVal;

};

};

Now, what’s even better, is that, since C++11, the restrictions over what types of variables could be put into an union. In case you didn’t know, in C++03, only types with trivial special member functions (copy constructor copy-assignment operator and destructor), could be put into unions. With C++11 this restriction got lifted and we can now put pretty much whatever types of variables we want into an union except reference types.

Armed with that knowledge, I could easily implement the abstraction over an interpreted value that I needed.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

class IVal

{

public:

// Possible value types of an AST node.

enum class ValueType { BOOLEAN, INTEGER, STRING, VOID, UNKNOWN };

public: // Constructors

IVal() : mType{ ValueType::UNKNOWN } { }

explicit IVal(bool val)

: mType{ ValueType::BOOLEAN }, boolVal{ val } { }

explicit IVal(int val)

: mType{ ValueType::INTEGER }, intVal{ val } { }

explicit IVal(const std::string& val)

: mType{ ValueType::STRING }, strVal{ val } { }

public: // Value accessors

bool GetBoolVal() const

{

assert(mType == ValueType::BOOLEAN);

return boolVal;

}

int GetIntVal() const

{

assert(mType == ValueType::INTEGER);

return intVal;

}

const std::string& GetStrVal() const

{

assert(mType == ValueType::STRING);

return strVal;

}

private:

ValueType mType; // Type of the IVal

union // Real value of the IVal

{

bool boolVal;

int intVal;

std::string strVal;

};

};

There! Job’s done! Let’s try it out.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int main()

{

std::string hello{ "Hello" };

IVal val1{ hello };

IVal val2 = val1;

}

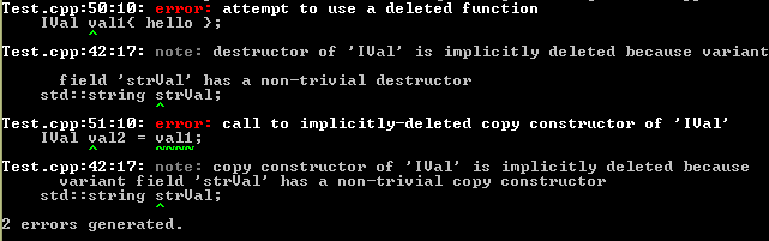

Delete everything

One thing I quickly realized was that every special member function of a class gets deleted the moment the moment you use an unrestricted union as a data member. So, basically, my IVal class looked like this to the compiler:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

class IVal

{

public:

/* ... */

public:

~IVal() = delete;

IVal(const IVal& val) = delete;

IVal& operator=(const IVal& val) = delete;

IVal(IVal&& val) = delete;

IVal& operator=(IVal&& val) = delete;

private:

/* ... */

};

What we’re left with is a situation were we have to deal with everything (assignment, destruction and initialization of members with non-trivial types) by ourselves.

Dealing with initialization

To initialize a union member with a non-trivial type we need to be able to explicitely construct it at its address in memory. Fortunately, C++ offers us something called placement new that does just that. To make sure that we can handle any new non-trivial type that might come our way, let’s encapsulate it in the following helper function:

1

2

3

4

5

template <typename T>

void Init(T& member, const T& val)

{

new (&member) std::string(val);

}

For those not familiar with the placement new syntax, you have to read it as follow:

- Create a

newvariable - At

member’s address - Whose type will be

std::string - And whose value will be

val

Dealing with destruction

Since any value with a non-primitive type will have been initialized through a placement new, it goes without saying that we will need to delete them explicitely. To help us doing so, let’s define a helper function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

void IVal::Destroy()

{

// We only have to handle the string case in this example

if (mType == ValueType::STRING)

{

// Using statement is necessary to compile with Clang

using std::string;

strVal.~string();

}

}

For those wondering, this bug is the one that causes trouble with Clang.

Dealing with assignment

Going with the hypothesis that everything that needed to be deleted beforehand has indeed been deleted, we can sum up the act of copying an IVal with the following function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

void IVal::Copy(const IVal& val)

{

switch (val.mType)

{

case ValueType::BOOLEAN:

boolVal = val.boolVal;

break;

case ValueType::INTEGER:

intVal = val.intVal;

break;

case ValueType::STRING:

Init(strVal, val.strVal);

break;

case ValueType::VOID:

break;

default:

assert(false); // Should never happen

}

mType = val.mType;

}

Putting it all together

All that’s left to do now is to define the special member functions that the compiler deleted by making use of the helper functions we just created.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

class IVal

{

public:

/* ... */

explicit IVal(const std::string& val)

: mType{ ValueType::STRING }

{

Init(strVal, val.strVal);

}

public:

~IVal() { Destroy(); }

IVal(const IVal& val) { Copy(val); }

IVal& operator=(const IVal& val)

{

// Nothing to do in case of self-assignment

if (&val != this)

{

// Goodbye old value...

Destroy();

// ...and hello new value!

Copy(val);

}

return *this;

}

private:

void AssignFrom(const InterpretedValue& val);

void Destroy();

template <typename T> Init(T& member, const T& val);

private:

/* ... */

};

Voila! Job’s done for real!

(And if you question me about how we could make IVal movable, let’s just say I’ve left this as an exercise to the reader :) )

The future

I do admit that this can be a bit more trouble than anticipated at first. For those that don’t want to go through the hassle, you’ll be happy to know that std::variant, which will bring a better sum type abstraction to the language, has been voted in for C++17. Let’s have a peek at what the future holds by rewriting our previous example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <utility>

using IVal = std::variant<bool, int, std::string>;

int main()

{

std::string hello{ "Hello" };

IVal val1{ hello };

IVal val2 = val1;

std::cout << std::get<std::string>(val2) << "\n";

}

Ain’t that neat.