Hey everyone!

This month marks the beginning of our journey into compiler development territory. For our first steps, we’ll start with an overview of modern compiler architecture and the development of a lexer capable of handling the TosLang programming language.

As you read along, you might notice that some details are missing from the programming examples. This is intended since some parts of what we are going to implement are quite trivial and repetitive and I didn’t want to obscure the examples by using macros or template metaprogramming. For the full code listing of the TosLang compiler, you just need to go here.

Now, without further ado, let’s dive into compiler development.

What’s in a compiler?

For most programmer a compiler is simply a program that transform the code they have written into an executable. How it achieves this however is a total mystery. In reality, there’s really nothing mysterious about the work a compiler does. It’s just that it’s just such a big piece of software involving so many aspects of software engineering that people often shy away from delving deeper and prefer to let someone else deal with it.

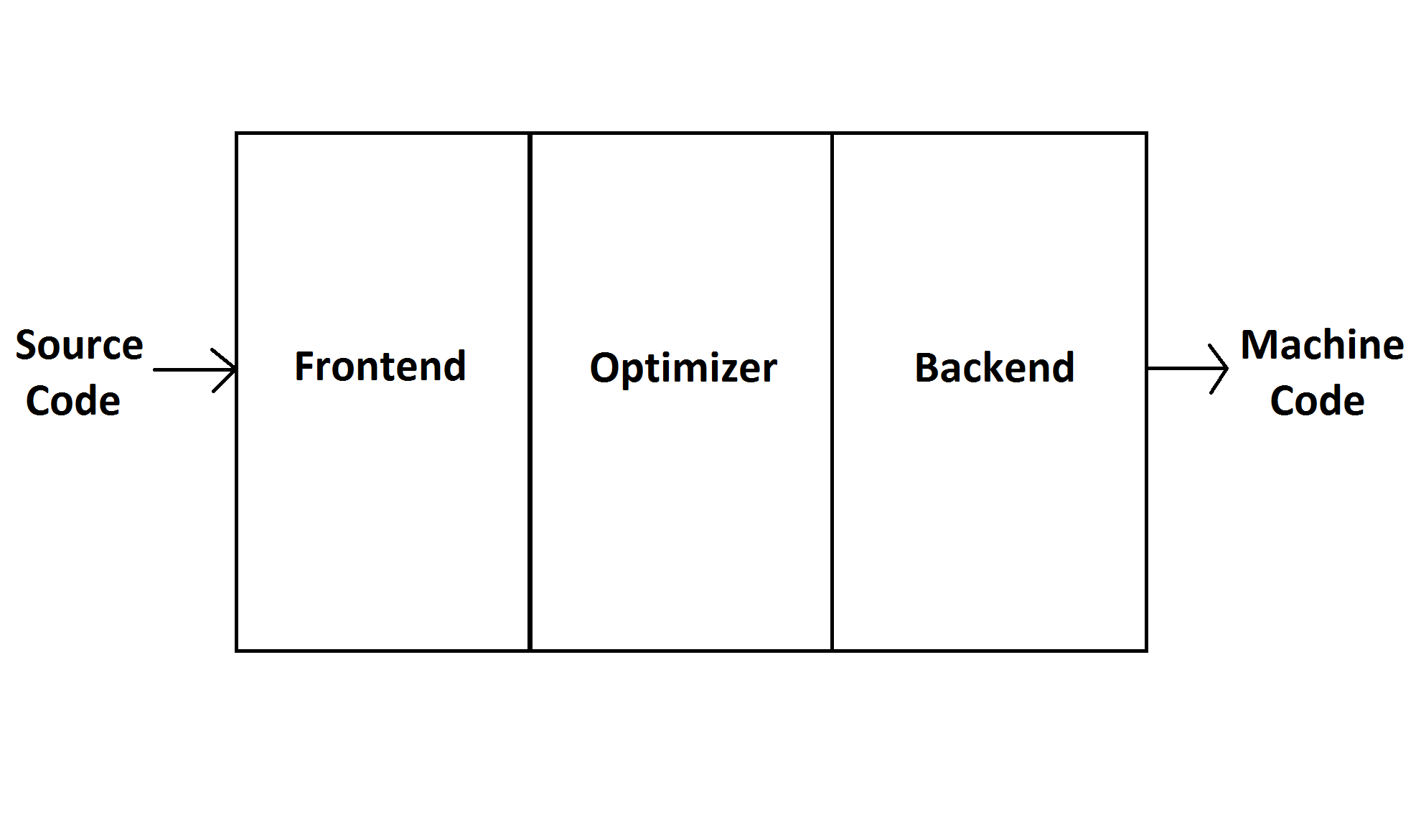

Let’s try to eschew the overcomplicated parts and present a high-level overview of a traditional static compiler. The most popular design for this kind of compiler is the three phase design as illustrated below.

I won’t go into every details here (as as everything will be explained as we implement the compiler) but what you have to know about each part is this:

- Frontend: Responsible for making sure the program respect the language specification. Can also perform some language-specific optimizations.

- Optimizer: Performs analysis and transformation on an intermediate representation of the program to optimize it. Since it works on an intermediate representation, the optimizations done here depends neither on the programming language not the target architecture.

- Backend: Performs optimizations based on the architecture the program is being compiled for and generate

The TosLang Compiler

Since TosLang is a statically typed language, its compiler will follow the three phase design. However, before even considering to implement one phase, we first need to define what the interface to the TosLang compiler is going to be. As we know, from a regular user point of view, what a compiler does, regardless of the language, is take a file name and use this information to produce an executable file through what may as well be black magic. Thus, as a starting point, I propose the following as a first draft for the TosLang compiler:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class Compiler

{

public:

void Run(const std::string& programFile);

private:

Lexer mLex;

};

What this’ll do is take a TosLang program filename and generate an executable with a arbitrarily chosen name (let’s say a.out). Next, let’s implement the Compiler::Run function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

void Compiler::Run(const std::string& programFile)

{

std::ifstream stream{ filename };

// Tough we are going to perform magic,

// we can't summon a program out of thin air

if (!stream)

{

std::cout << "Can't open " << programFile << std::endl;

return;

}

std::string buffer{ std::istreambuf_iterator<char>(stream),

std::istreambuf_iterator<char>{} };

std::vector<Token> toks = mLexer.Tokenize(buffer);

// Further arcane incantations to come...

}

Notice that I’m using std::istreambuf_iterator to fetch the content of the file and build my buffer. The reason behind this choice is that we want the raw unformatted string representing the program and we want it fast which is exactly what we’re going to get by using this iterator.

After the buffer has been filled, the next thing the method does is build a sequence of tokens out of the buffer. The next section offers insight as to why this must be done.

What does a lexer do anyway?

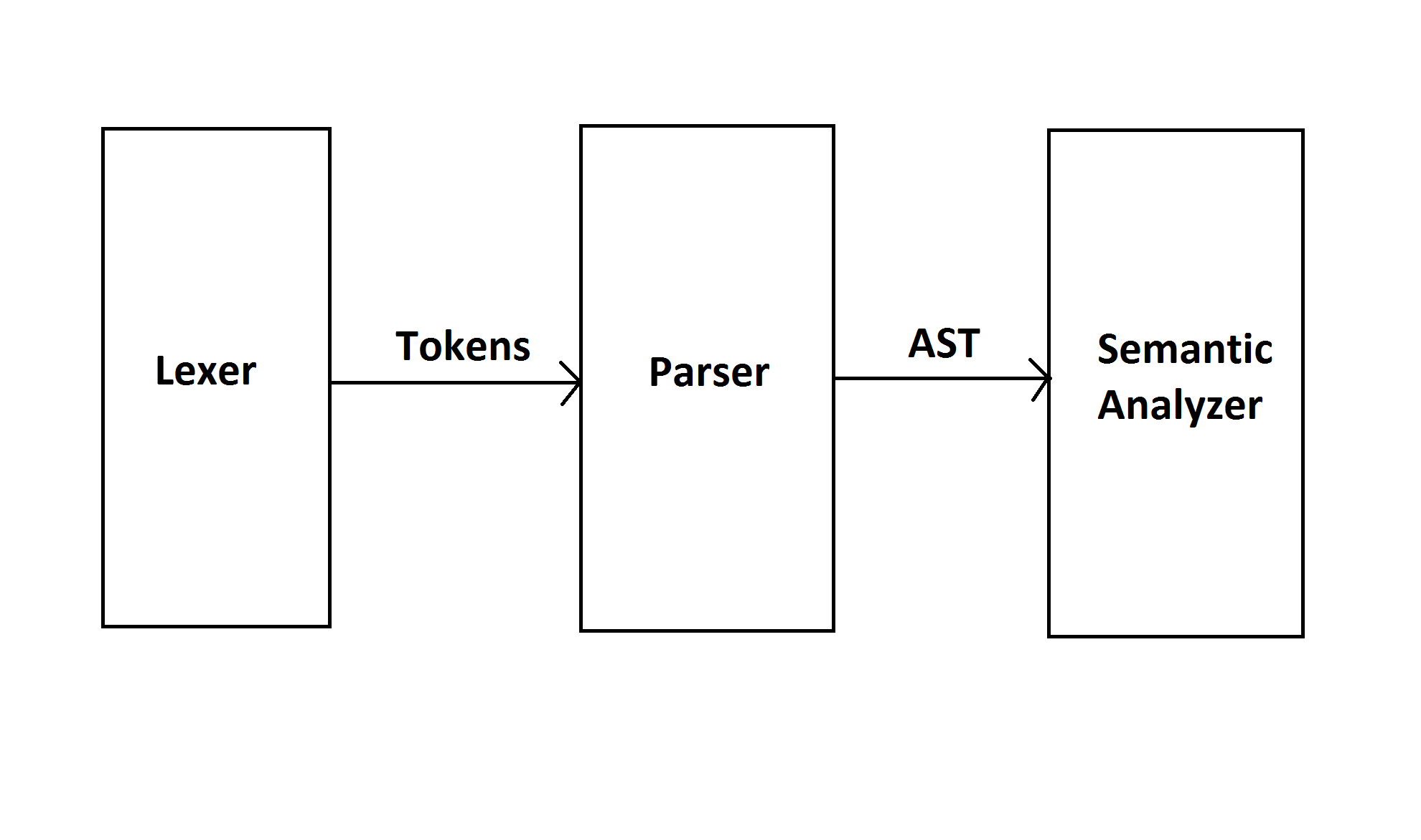

Let’s zoom in on the on the compiler design picture.

As I mentionned a compiler frontend has the responsibility of making sure the program respects the specification of the language it is written with. To do so, it must ask and answer the three following questions: What is being written? Does it respect the language’s grammar? And does any make sense?

The role of the lexer is to answer the first of these questions. So for each element of the program the lexer has to identify what elements of the programming language are being used. Is is a integer literal? Is it a keyword? If so, which is it? Each time it finds an answer, a token will be associated with the program element (keyword, identifier, operator and so on). Thus, when it has gone over all the program, it will have a sequence of tokens to give off to the next phase of the frontend i.e. the parser.

Implementation

The first part of the implementation of a programming language is to define what tokens will there be to identify. For TosLang, the tokens will be as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

enum class Token

{

// Keywords

FUNCTION, IF, PRINT, RETURN, SCAN, SPAWN,

SYNC, TYPE, VAR, WHILE,

// Boolean values

FALSE, TRUE,

// Operators

AND_BOOL, AND_INT, DIVIDE, EQUAL, GREATER_THAN,

LEFT_SHIFT, LESS_THAN, MINUS, MODULO, MULT,

NOT, OR_BOOL, OR_INT, PLUS, RIGHT_SHIFT,

OP_START = AND_BOOL, OP_END = RIGHT_SHIFT,

// Misc

ARROW, COMMA, COMMENT, COLON, IDENTIFIER,

LEFT_BRACE, LEFT_BRACKET, LEFT_PAREN,

ML_COMMENT, NUMBER, STRING_LITERAL, SEMI_COLON,

RIGHT_BRACE, RIGHT_BRACKET, RIGHT_PAREN,

// End of file

TOK_EOF,

// Unknown

UNKNOWN

};

Next, let’s define the interface of the lexer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

class Lexer

{

public:

// Insert program, get tokens

std::vector<Token> Tokenize(const std::string& programStr);

};

I know this doesn’t require a class for the moment. But trust me, it will grow sooner than later.

Now, let’s dive into the lexer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

std::vector<Token> Lexer::Tokenize(const std::string& programStr)

{

// Can't extract tokens from nothing

if(programStr.empty())

return {};

// What we'll produce

std::vector<Token> toks;

// What we'll use to go through the program

auto programIt = programStr.begin();

// Will be used a lot, so we better put it in a variable

auto programEnd = programStr.end();

// Taking the locale into account

std::locale loc{""};

while(programIt != programEnd)

{

// Skip over whitespaces

while (programIt != programEnd && isspace(*programIt, loc))

++programIt;

// End of file, we're done

if (programIt == programEnd)

return Token::TOK_EOF;

// Caching the current char because we will use it A LOT

const char currentChar = *programIt;

switch (currentChar)

{

case ',':

++programIt;

toks.push_back(Token::COMMA);

break;

// Lots of similar cases for simple one character tokens

default:

// We have a token coming from a more complex pattern,

// let's find out what

std::string currentStr;

// If this starts with a letter,

// it is either a keyword or an identifier

if (isalpha(currentChar, loc))

{

// Let's greedily build a string with the pattern

currentStr = currentChar;

// We accept alphanumeric characters because it is legal for a

// function or variable identifier to contains number

while (++programIt != programEnd && isalnum(*programIt, loc))

currentStr += *programIt;

if (currentStr == "fn")

toks.push_back(Token::::FUNCTION);

// Other cases where the pattern directly match

// a keyword token...

else

// If this doesn't match a keyword,

// then it is a simple identifier

toks.push_back(Token:::IDENTIFIER);

}

// It starts with a digit, then it can only be a number

else if (isdigit(currentChar, loc))

{

// Eat up all the digits making up the number

while (isdigit(*(++programIt, loc)));

toks.push_back(Token::NUMBER);

}

else

{

// The hell is that?

toks.push_back(Token::UNKNOWN);

}

}

}

return toks;

}

Result

In the end, our lexer will be able to take a TosLang program like the one below:

1

2

3

4

fn main(i : Int) -> Void {

print "Hello World!";

return;

}

and produce the following output:

[FUNCTION], [IDENTIFIER], [LEFT_PAREN], [IDENTIFIER], [COLON], [TYPE], [RIGHT_PAREN], [ARROW], [TYPE], [LEFT_BRACE], [PRINT], [STRING_LITERAL], [SEMI-COLON], [RETURN], [SEMI-COLON], [RIGHT_BRACE]

This about sums up the first step toward developing a full-fledged compiler for the TosLang programming language. While this doesn’t look like much for the moment, this development is crucial for what is coming up later.

Also, before I’m being reproached of being a poor developper, I am fully aware that there’s currently zero error handling done in the lexer. So if someone wanted to put a letter in the middle of a number (like this: 123b456), this would immediately result in a wrong output. However, fear not my young padawans, we will deal with error handling later down the road. This example only purpose was to demonstrate how a simple lexer could be implemented.

Coming up next month: Designing an AST