Note 1: What I’m presenting here is evidently not a production grade tool. In fact, I’d say it barely even qualify as a proof of concept. If you really want to debug multithreaded programs, please use a tool like Intel Inspector, ThreadSanitizer or Helgrind.

Note 2: While everything here is presented in C++, the algorithm that I’m describing could be implemented and used to detect data races in any other programming language.

Story time

At my job, I sometimes have to rely upon a race detection tool to figure out why the hell threads aren’t behaving I as expect them to. While it is nice to have something readily available to help you in such cases and not having to think about how you could debug a multithreaded program, I couldn’t help but wonder, how do these kind of tools actually works? And as you know, curiosity is always a good reason to start a programming project.

What’s a data race?

By definition a data race occurs when two or more threads access the same memory location without any locking mechanism and at least one of them is a write access. As an example, take a look at this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

size_t data = 0;

std::vector<std::thread> threadVec;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

{

threadVec.emplace_back([&data]()

{

for (int j = 0; j < 100000; ++j)

{

++data;

}

});

}

Pop quiz: what’s the value of data when all threads are finished?

Answer: Something between 0 and 1000000. We can’t say which value precisely because there are way too many unsynchronized accesses to data.

This goes to show that, as in real life, if you don’t use protection you’re bound to catch some bugs.

(However, compilers can exploit the fact that a data race induces undefined behavior in the program and remove the threads altogether leaving only the incrementation of the variable in the outputted binary.)

Keeping track of memory accesses

One of our first job will then be to create a structure to help us keep track of memory accesses. Here’s what I propose:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

using TID = std::thread::id;

struct ShadowState

{

TID AccessorID;

size_t AccessorClock;

bool IsWrite;

};

std::unordered_map<void*, ShadowState> MemoryState;

Going in reverse order, we first have the MemoryState structure that will associate a memory location with a ShadowState. It goes without saying that this structure will be at the heart of our race detection algorithm.

Next, we have the ShadowState structure which will keep some interesting informations about a memory access. It will tell us if the access was a write access through the IsWrite data member (needed because reads alone can’t cause a data race). It will also indicate which thread is doing the access by keeping its ID (AccessorID). Finally, it will tell us at which point in the accessor’s thread’s clock the access happened. This will be crucial to establish (or not if there’s a race) a happens-before relation between two memory access.

A clock for multithreaded program

When diving into the world of parallel programming, one thing you have to realize is that you can’t cling to your old notions about time. Things won’t happen at a precise moment in time like they used to in sequential programs. There’s now a non-determinism in our programs that makes ordering events a much more complicated matter.

So how do we make sense of the events? How do we establish a relation between two events in a multithread context?

One way to do so is by using vector clocks. The basic principle behind these clocks is that each thread will possess a series of clock that will keep track of the time of every thread in the system in terms of memory access and synchronization events. Also, and probably more importantly, all the clocks in a given vector clock will only have the values that the owner thread can perceive at a given moment.

Sounds too complicated? Let’s try again with an example. For this, we’ll be using a simplified version of the data race example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

size_t data = 0;

std::vector<std::thread> threadVec;

// Starting T1

threadVec.emplace_back([&data]() { ++data; });

// Starting T2

threadVec.emplace_back([&data]() { ++data; });

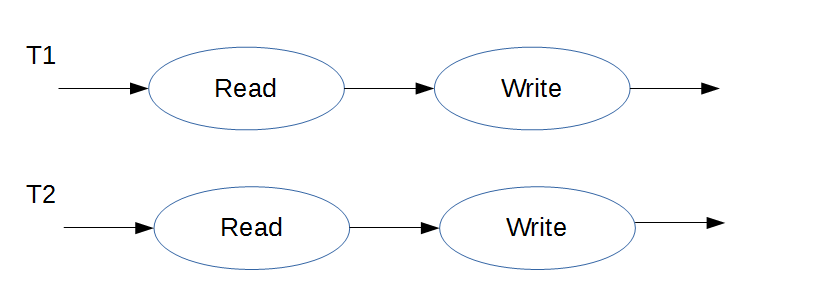

Now let’s draw a picture of what’s happening in this program with regards to accesses to the data variable:

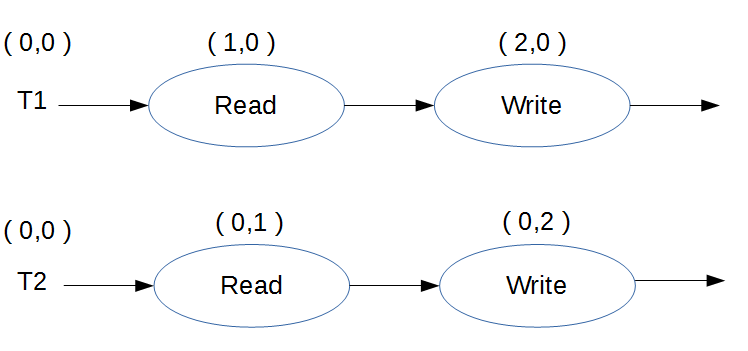

Next, let’s introduce vector clocks in the picture:

As you can see, each thread has in its possession a series of clock that are incremented with each memory access. Since there is no synchronization between threads, they do not communicate their clock’s states with each other.

The happens-before relation

A happens-before relation is an ordering relation between two memory accesses. Having such a relation means that whatever the order in which the other memory accesses in a given program will be executed (remember multithreading introduces non-determinism in a program), the two accesses that shares this relation will always happen in the order prescribed by the relation. To determine that such a relation is present between two memory access, you only have to look at their vector clocks. If one of the access’ clocks’ values are all inferior to the other’s clocks’ values, then we have a happens-before relation.

With the happens-before relation defined, we can now produce an algorithm to detect data races in a program. Basically, we’ll say that there’s is a data race if these 3 criteria are met:

- They must happen on different threads (Obviously, you can’t race with yourself!)

- One of the accesses must be a write (We can’t have races with just read)

- We can’t define a happens-before relation between the events (No ordering means a lack of synchronized accesses)

If we look at our previous example through this algorithm, we can clearly see that it doesn’t respect the third criteria. This should serve as proof that the proposed criteria are enough to prove that a program contains data race.

Implementing happens-before

Obviously, for implementing happens-before, we’ll need an abstraction descibing a vector clock.

1

2

3

4

5

using ThreadClock = std::unordered_map<TID, size_t>;

std::unordered_map<TID, ThreadClock> ThreadStates;

std::atomic<int> ConcurrentAccessCount{ 0 };

With ThreadClock I can then define ThreadStates which will help keep track of the each thread vector clock. Of course, this isn’t really a good practice to have such a global variable, but for rapid prototyping, I’d say that we can make an exception. Another thing I’ve added is a counter that will keep track of how many concurrent accesses have been performed during the program’s execution.

With this, we have all we need to implement our race detection algorithm.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

void CheckForConcurrentAccess(const ShadowState& oldState,

const ShadowState& newState)

{

// Condition 1:

// You can't race with yourself

if (oldState.AccessorID == newState.AccessorID)

{

return;

}

// Condition 2:

// For a data race to occurs we need at least one write access

if (!oldState.IsWrite && !newState.IsWrite)

{

return;

}

// Condition 3:

// A data race happens when not every element of the current

// accessor's vector clock is less than the corresponding element

// in the previous accessor's vector clock.

auto happensBefore = [](ThreadClock& eventClock1,

ThreadClock& eventClock2)

{

return std::all_of(

eventClock1.begin(), eventClock1.end(),

[&eventClock2] (const std::pair<TID, size_t>& thread1Time)

{

return thread1Time.second <= eventClock2[thread1Time.first];

});

};

ThreadClock& currAccessorClock = ThreadStates[newState.AccessorID];

ThreadClock& prevAccessorClock = ThreadStates[oldState.AccessorID];

// Can we order the two accesses with a happens-before relation?

if (!happensBefore(currAccessorClock, prevAccessorClock)

&& !happensBefore(prevAccessorClock, currAccessorClock))

{

ConcurrentAccessCount.fetch_add(1);

}

}

Funneling reads and writes

Since this is a prototype that we’re writing, instead of instrumenting the program’s binary, we will propose an interface to keep track of the read and write event of the program.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

template <typename T>

T Read(T&& val)

{

// Incrementing the current thread clock

const TID currentTID = std::this_thread::get_id();

++ThreadStates[currentTID].Clock[currentTID];

// Checking for potential race condition

ShadowState newState{currentTID, ThreadStates[thisTID].Clock[thisTID],/*IsWrite=*/false};

CheckForConcurrentAccess(MemoryState[&val], newState);

MemoryState[&val] = newState;

return val;

}

template <typename T>

void Write(T& oldVal, T&& newVal)

{

// Incrementing the current thread clock

const TID currentTID = std::this_thread::get_id();

++ThreadStates[currentTID][currentTID];

// Checking for potential race condition

ShadowState newState{currentTID,

ThreadStates[currentTID][currentTID],

/*IsWrite=*/true};

CheckForConcurrentAccess(MemoryState[&oldVal], newState);

// Writing new values

MemoryState[&oldVal] = newState;

oldVal = newVal;

}

Let’s put it to the test

Let’s write a racy program that makes use of the race detector interface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

int main()

{

int data = 0;

std::vector<std::thread> threadVec;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i)

{

threadVec.emplace_back([&data]()

{

Write(data, data + 1);

});

}

for (auto& th : threadVec)

{

if (th.joinable())

{

th.join();

}

}

std::cout << "Concurrent accesses found: "

<< ConcurrentAccessCount.load()

<< std::endl;

}

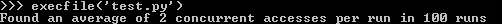

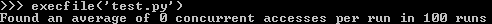

This should do it. Let’s see what we got after some test runs using a Python test script.

It works!

What about locks?

Memory accesses aren’t the only things that we can track using vector clocks. Synchronization events like locking or unlocking a mutex are also an important part of the happens-before framework that we’re building. In fact, they are the means by which threads will communicate their vector clocks information between each other.

Let’s illustrate what I mean by an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

size_t data = 0;

std::vector<std::thread> threadVec;

std::mutex mut;

// Starting T1

threadVec.emplace_back([&data](){ mut.lock(); ++data; mut.unlock(); });

// Starting T2

threadVec.emplace_back([&data](){ mut.lock(); ++data; mut.unlock(); });

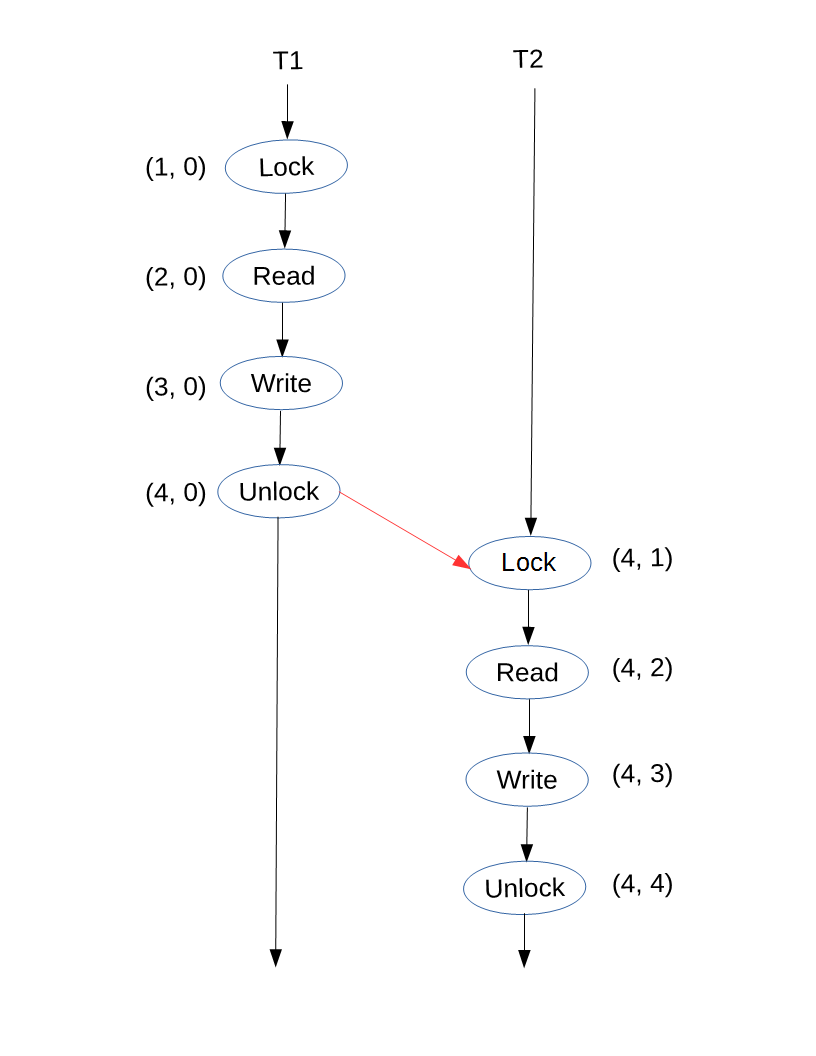

This program can be represented as follows (vector clocks and all):

Note that this is only one of the two possible orderings of this program. But regardless of the ordering chosen for this example, the fact remains that we can now establish a happens-before relation between the accesses to data. As you know, only one thread can acquire a mutex at a time. This means that the other thread that wants the mutex will come to a halt while waiting for it. What’s probably new is that when a thread acquires the mutex, it will also acquire the most up to date clocks’ states that the mutex has seen so far.

A mutex for our race detector

Our mutex implementation will be quite minimal. It will wrap a std::mutex and will keep a ThreadClock to help transmit clocks’ states between threads.

1

2

3

4

5

6

class Mutex

{

private:

std::mutex mMutex;

ThreadClock mClock;

};

Unlocking our mutex will update both the mutex’ and the current thread’s clock.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

void Unlock()

{

const TID thisTID = std::this_thread::get_id();

ThreadClock& accessorClock = ThreadStates[thisTID];

// Update the accessor clock and mutex clock

++accessorClock[thisTID];

mClock[thisTID] = accessorClock[thisTID];

mMutex.unlock();

}

While locking the mutex, we will proceed to update the mutex’ and current thread’s clocks. This will be done by assigning the maximum value of a clock to both the mutex’ and the current thread’s vector clock.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

void Lock()

{

mMutex.lock();

const TID thisTID = std::this_thread::get_id();

ThreadClock& accessorClock = ThreadStates[thisTID];

++accessorClock[thisTID];

// During a receive event, we synchronize the accessor clock with

// the mutex clock. Afterwards, both will have the most up to date

// vector clock possible.

mClock.insert(accessorClock.begin(), accessorClock.end());

for (auto& thTime : mClock)

{

const size_t maxClockTime = std::max(accessorClock[thTime.first], thTime.second);

thTime.second = maxClockTime;

accessorClock[thTime.first] = maxClockTime;

}

}

Does this still work?

Taking our previous test and inserting proper synchronization in it will result in this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

int main()

{

int data = 0;

std::vector<std::thread> threadVec;

Mutex mut;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i)

{

threadVec.emplace_back([&data, &mut]()

{

mut.Lock();

Write(data, data + 1);

mut.Unlock();

});

}

for (auto& th : threadVec)

{

if (th.joinable())

{

th.join();

}

}

std::cout << "Concurrent accesses found: "

<< ConcurrentAccessCount.load()

<< std::endl;

}

Taking it for run with the same Python test script as before yields:

It stil works!

What do “real” race detectors do?

What I’ve just shown you is a basic framework for something that is called pure happens-before race detection. While it is a good start for a race detector, it is by no means a perfect solution. For one, it is way too much intrusive. Also, since it’s a dynamic race detector, its results will greatly vary depending on the given execution order of a program. This could go as far as declaring a program race-free when it isn’t.

In real life, the race detectors that I know of often work by instrumenting the binary produced from a program. This means that all those loops our test programs had to jump through by using a cumbersome interface aren’t required. Instead, the compiler will put them in place for directly in the program’s binary.

It also goes without saying that they use much more powerful algorithms than what I’ve shown here. From what I can gather, their algorithms often are a mix combining more advanced happens-before-based race detection algorithms and other algorithms based on correct mutex use. Some even throw sampling into the mix. This goes to show that rabbit hole of race detectors still goes deeper than what I’ve presented in this post.

The more you know

- All the code for this article can be found here.

- This post draws most of its inspiration of from Kavya Joshi’s “go test -race” Under the Hood. Basically, I just wanted to have a concrete implementation of the content of that presentation.

- If you want to know more about vector clocks, you have to read Leslie Lamport’s seminal papers: Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System

- When defining the

ShadowStatestructure, what I’m really doing is implementing probably the most rudimentary form of what is called shadow memory. A good article to wrap your head around this concept is How to Shadow Every Byte of Memory Used by a Program - For those that want to explore other approaches to race detection, I suggest reading LiteRace: Effective Sampling for Lightweight Data-Race Detection which attacks the problem from a more statistical angle.