All the code for the articles in this series can be found here.

Now that the users can create a new repository through the init command, we can start filling it out. This will be the purpose of the add command that we’ll look at in this article.

Interface

As was the case with the init command, I strived to make the requirements for the add command as minimal as possible. Consequently, in my original assignment, I asked that the command only take a single input: the relative path of the file a user wants to add to the repository. Of course, if students wanted to make the command work with a directory path as well (to perform mass additions), they were free to do so. However, I didn’t feel as if this would gave them additional insights into what goes into adding files to a repository. Thus, the interface to implement is the following:

1

dvcsus init <filepath>

Staging Database

Before going into implementation details, let’s talk about databases. Remember that in the last article, I quickly went over the fact that DVCS would be implemented using two databases; one for the repository proper and one to store the current local state. It goes without saying that the add command will have an impact on the local state of DVCS. Therefore, let’s look at what goes into the Staging database.

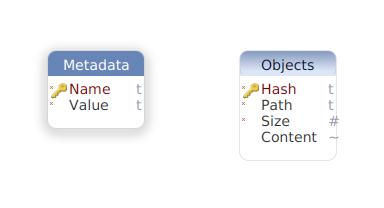

Metadata

The Metadata could be considered a key-value store inside the database. Its purpose is to store any information about the current state of the repository that’ll never put into the repository proper (the Repository database that we’ll look at in the next article). There’s not much else to say here since the add command doesn’t interact with this table.

Objects

This is the core of the Staging database. Basically, a file in a DVCS repository will be stored in an object format similar to Git’s. The reasoning behind each element of this format is as follow:

- Hash: A SHA1 hash of the compressed contents of a file. In other distributed source control systems this would have a dual purpose: validate the data associated with the object and guide the system as to where the object should be stored on disk. Obviously, in DVCS, we don’t need the hash to indicate where to store objects since everything is stored in databases. However, we still want to be able to validate objects’ contents which is why we store a hash.

- Path: Relative path of a file to the root repository directory. This will tell us where to write the uncompressed object data of a file on disk should we want to clone a repository.

- Size: Size of the uncompressed file contents. This is another mean by which we’ll validate the object’s content. Should the unzipped Content field data be anything other than the value stored in this field, we’d know something went wrong.

- Content: Blob containing the compressed contents of a file.

Adding objects

While I won’t go into the details of how to store an object into the staging database (it basically boils down to preparing an SQL statement and subsquently executing it against the DBMS of your choice), there are some details as to how to build an object that I think are worth getting into. First, let’s look at some code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

template <typename TStream> requires std::derived_from<TStream, std::istream>

HashedCompressedData PrepareObjectContent(TStream &inputStream)

{

RETURN_IF(!inputStream.good(), {});

namespace bios = boost::iostreams;

using OutputDevice = bios::back_insert_device<std::vector<char>>;

using OutputStream = bios::stream<OutputDevice>;

std::vector<char> contents;

OutputDevice device{contents};

OutputStream objectStream{device};

bios::filtering_streambuf<bios::input> objectCompressingStream;

objectCompressingStream.push(bios::zlib_compressor());

objectCompressingStream.push(inputStream);

try

{

objectStream.exceptions(std::ios::badbit | std::ios::failbit);

bios::copy(objectCompressingStream, objectStream);

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

fmt::print(std::cerr, "{}\n", e.what());

return {};

}

return {ComputeSHA1(contents), std::move(contents)};

}

Right off the bat, you can see that I decided to go with a stream-based interface. The reasons behind this choice are:

- For performance reason, I wanted the processing done on a file to stay in memory as much as possible. This naturally disqualified all possibilities to have a path-based interface where a file would be opened and read time and time again.

- I wanted to have the possibility to implement test commands where the contents to store would come from the standard input if I wished to. Sure, this could be done by having two separate implementations of the

PrepareObjectContentfunction. However, this would be wasteful since a stream-based interface can elegantly handle all aforementioned use cases.

Once this choice was made, I still needed to put some restrictions in place. I couldn’t just accept any stream. For example, receiving an output stream just wouldn’t do. In fact, it would probably result in a compiler error that’d look like something straight out of the Necronomicon. This is where concepts come into play. For those you don’t know, concepts are a feature introduced in C++20 that allow us to put some requirements on a template parameter. (For those that want to know more, I encourage you to watch this great CppCon presentation.) In our specific case, this will enable us to tell the compiler that only input stream can be accepted by the PrepareObjectContent function. If someone tries to give it something else that doesn’t meet this requirement, then the compilation will fail with a nice error message telling them how they didn’t respect the contract of the function.

Next, I’ll briefly mention that I had to resort to Boost.Iostreams to compress the stream’s data. As the C++ standard doesn’t offer such a functionality, I had to look somewhere else. This did reinforce my confidence in my choice to use streams: everything fitted together very nicely.

Finally, there’s the matter of dealing with streaming errors. The problem with standard streams is that the way they report error is less ideal. As soon as there’s a problem, they’ll set some bit to indicate what’s wrong. Afterward, you have to interrogate the streams to know if it’s still good or if there’s a problem with it. There’s no method or function that would take a standard stream and return you a clear indication as to whether or not the operation has succeeded. Worse still, these error bits stick. This means that you not only have to interrogate the stream, you have to clean it if you want to reuse it. To avoid such concerns, I decided to go with the nuclear option: I asked the stream to throw an exception if it went bad. Moreover, I’ll have a somewhat informative message to show the user through the exception message. It still seems a bit too much for my taste, but it works!

Up next, we’ll transform the staged objects into commits.