How hard could it be to produce an executable out of some C++ files?

Compiling a C++ application (the wrong way)

A knee-jerk response to the question could be: “Not much! I just need to compile each of the files and then link the resulting object files together into an executble. There, done!”

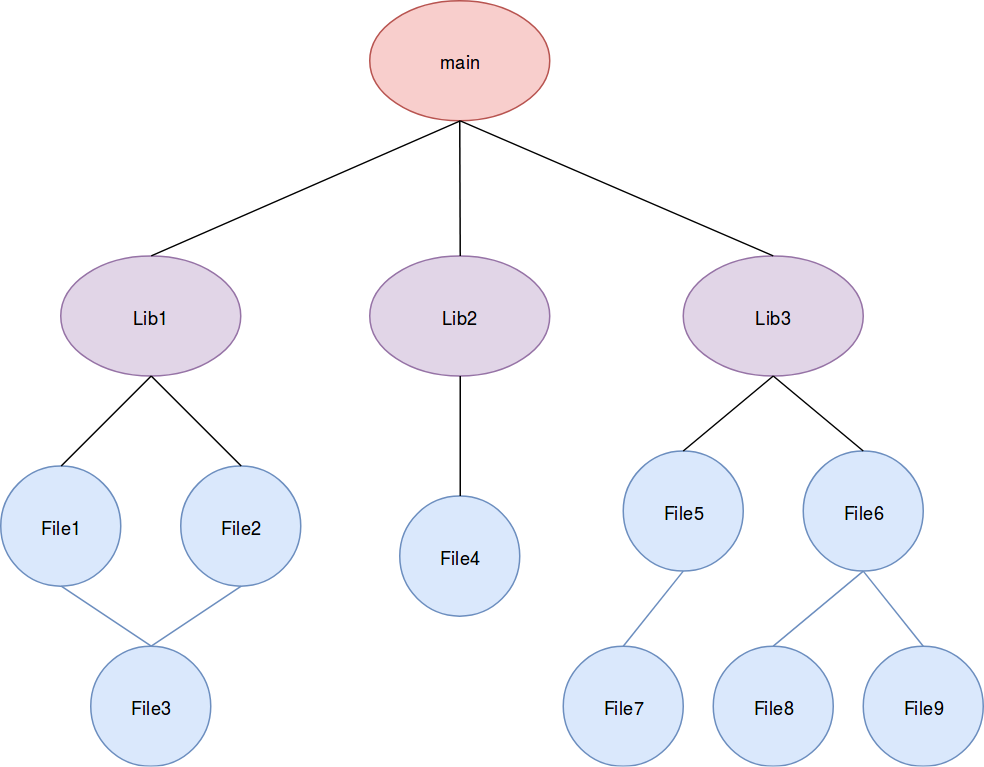

Imagining for a moment that these source files are laid out in a folder hierarchy similar to the one shown in the introductory post of this series, such an approach could be put into code in the following way:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

namespace fs = std::filsystem;

void CompileToExecutable(const std::string& rootDir,

const std::string& execName)

{

std::vector<std::string> objFiles;

for(const auto& dirEntry

: fs::recursive_directory_iterator(rootDir))

{

if(!IsCPPFile(dirEntry))

{

continue;

}

objFiles.push_back(CompileToObj(dirEntry));

}

LinkExecutable(objFiles, execName);

}

This might just work for the most basic of programs. But it might fail spectacularly for just about everything else.

The problem at the heart of this algorithm is that it doesn’t take into consideration the possible dependencies between the different parts of the source code. As Ernest Hemingway once said: “No C++ file is an island”.

For instance, take the case of an onion-like codebase where multiples libraries are organized into several layers of abstractions. Generally, the upper layers will make use of the lower layers to build up their abstractions. It thus follows that, when compiling, you’d want the lower libraries to be compiled first so their symbols can be made available to the upper libraries. Failing to do so will undoubtedly result in a cornucopia of compiler and linker errors that will keep on piling up with no end in sight. Naturally, having that happen too often can send a normal programmer into a table-flipping fury and you wouldn’t want to live through that.

Dependency Graph

The go-to solution to express dependencies in computer science is, as the above subtitle indicates, the dependency graph.

In our current scenario, we’ll have the nodes represent either object files resulting from compilation, library files to be produced or the executable to be assembled (respectively blue, purple and red nodes). Between these nodes, we’ll insert edges to signify that an artifact depends on another artifact to be produced. For example, don’t create a library file before all the object files that should go into it have been produced.

Dependency Graph Construction

Building a dependency graph is surprisingly easy. let me walk you through it. First, we need to add the program’s entry point to the graph. As you’ll see later, this will constitute the graph’s root node. In our hypothetical source code structure, this correspond to the main.cpp file right at the top.

1

2

3

4

5

DependencyGraph BuildDepGraph(const std::string& rootDir,

const std::string& entryPoint)

{

DependencyGraph graph;

graph.AddNode(entryPoint);

Next, we’ll add a node for each the folder adjacent to the entry point file. These will represent libraries to be built by our build system.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

for(const auto& rootDirEntry : fs::directory_iterator(rootDir))

{

// Skipping over the main.cpp file

if(!fs::is_directory(rootDirEntry))

{

continue;

}

const std::string curDirname = rootDirEntry.path().string();

graph.AddNode(curDirname);

Afterwards, we’ll look into each of the files in each of the folder to extract their dependencies and link them up in our graph.

Note that, for the sake of simplicity, we’ll assume that inter-library dependencies do not exist. Moreover, astute readers will notice that a graph built using the code below will be quite dense. This is intentional since I wanted to present the simplest algorithm possible. It’s definitly possible to make the graph sparser either by using another algorithm or running a post-processing step on the produced graph.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

for(const auto& dirEntry : fs::directory_iterator(rootDirEntry))

{

// Only files that actually get built are of interest to us

if(!IsCPPFile(dirEntry))

{

continue;

}

const std::string curFilename = dirEntry.path().string();

graph.AddNode(curFilename);

for(const auto& dep : GetDependencies(curFilename))

{

graph.AddDependency(dep, curFilename)

}

graph.AddDependency(curFilename, curDirname);

}

Finally, when we’re done with a folder, we’ll link up its associated node with the root node i.e. the program’s entry point.

1

2

3

4

5

graph.AddDependency(curDirname, entryPoint);

}

return graph;

}

Dependencies Extraction

To extract the dependencies of a .cpp file, there’s nothing quite like a bit of regex-y magic. Take a .cpp file, open it up, apply spells written in an occult language that look like something out of the Necronomicon (or, worse, that look like a Perl program) and you get your dependencies.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

using Dependencies = std::vector<std::string>;

Dependencies GetDependencies(const std::string& sourceFile)

{

// Will match any include regardless of delimiter.

// However, it'll only match .h and .hpp files.

// The matched include (e.g. test\test.h) will be

// in the 3rd capture group

const std::regex includeRx{

"#include (\"|<)([a-zA-Z0-9\\\/]+\.hp{0,2})(\"|>)" };

Dependencies deps;

std::ifstream fileStream{ sourceFile };

const std::string fileContent{

std::istreambuf_iterator<char>{ fileStream },

std::istreambuf_iterator<char>{} };

auto rxIt = std::sregex_iterator(fileContent.begin(),

fileContent.end(),

includeRx);

auto rxEnd = std::sregex_iterator{};

for(; rxIt != rxEnd; ++rxIt)

{

const std::string implFile = GetImplFile(rxIt->str(2));

if (!implFile.empty())

{

deps.push_back(implFile);

}

}

return deps;

}

Tooling

When you’re a software developper, laziness is always an option. Therefore, I’d be remiss (or just plain lazy thus illustrating my point) if I didn’t mention that there are tools available to automatically extract source code dependencies. The one that I want to talk about, because it’s the most obvious, is the compiler. With the right switch, you can make it spit out. In the case of gcc, this switch is MMD.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

project

│ main.cpp

│

└─test1

│ │ test1.cpp

│ │ test1.h

│

│ test2.cpp

│ test2.h

Take the above project. To extract the dependencies within, one could invoke gcc as follows.

1

g++ test1.cpp test2.cpp main.cpp -o main -fsyntax-only -MMD

The result of this compiler invocation will be a main.d file with the following contents.

1

main: main.cpp test2.h test1/test1.h

If parsing a single file is more up your alley then you should seriously consider this option. You can’t go that wrong with it. The compiler is the Big Brother of your source code; he knows about source files and their close ones.

Lastly, before I start rambling on too much, this is but one option if you want to defer dependencies extraction to an external tool. If you’d prefer to go with something else, I’m sure you can find what you need if you make the effort.

Coming up next: Nice graph, but what can you do with it?